Australian Rockmaster damselflies

Diphlebia

Rockmasters: Australia’s Giant Damselflies

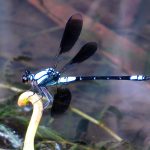

If you are exploring a rocky creek or a rainforest stream in eastern Australia and see a large, electric-blue insect resting on a boulder, you have likely met a Rockmaster.

Belonging to the genus Diphlebia, these are some of Australia’s most spectacular and robust damselflies. However, they are famous for confusing observers! Because of their thick bodies and their habit of resting with wings spread flat, they are frequently mistaken for dragonflies.

This guide will help you identify the five distinct species of Rockmaster found in Australia, understand their connection to our waterways, and appreciate their role in the ecosystem.

Is it a Dragonfly or a Damselfly?

The Rockmaster breaks the usual rules of identification.

- The “Dragonfly” Look: They have thick bodies and hold their wings out to the sides (unlike most damselflies that fold them back).

- The “Damselfly” Truth: If you look closely, their eyes are widely separated (like a hammerhead shark), and their forewings and hindwings are virtually identical in shape. These are classic damselfly features.

Indigenous Connection: Sentinels of the Water

For tens of thousands of years, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have observed the cycles of nature. While specific stories vary between language groups, dragonflies and large damselflies are often viewed as important indicators of seasonal change and the health of freshwater Country.

In many cultures, the presence of these insects signifies that the water is healthy and life-sustaining. Some traditions view them as messengers, moving between the water (the spirit realm) and the air. When you see a Rockmaster patrolling a stream, acknowledge that you are standing on Country that has been cared for since the Dreaming.

1. The Sapphire Rockmaster (Diphlebia coerulescens)

The Classic Southern Beauty

This is the most well-known species in the south-east. It is the “jewel” of rocky rivers.

- Where to find them: South-east Queensland, New South Wales, and Victoria. They love clean, fast-flowing freestone rivers.

- Identification (Male):

- Thorax: Black with two broad, vivid blue stripes on top.

- Abdomen: Mostly black, but with significant blue markings near the tip.

- Wings: Often have a brownish/smoky patch near the “knot” (nodus) on the leading edge.

- The Female: Cryptic colouring of olive-green or brown to blend in with mossy rocks.

Quick ID Tip: If you are in NSW or Victoria and see a blue-striped thorax, it’s likely the Sapphire.

2. The Tropical Rockmaster (Diphlebia euphaeoides)

The Northern Giant

Heading north into the tropics? This is the Sapphire’s heavier, darker cousin.

- Where to find them: North Queensland (Wet Tropics) and extending into New Guinea. Look near waterfalls and rainforest swimming holes.

- Identification (Male):

- Thorax: Similar blue stripes to the Sapphire.

- Abdomen: This is the key difference. The abdomen is almost entirely black, with only very small, restricted blue spots.

- Wings: Usually hold their wings very flat and rigid.

- The Female: Golden-brown or yellowish, often found high in the vegetation surrounding the water.

Quick ID Tip: If you are north of Townsville and the tail looks very black, it’s a Tropical.

3. The Whitewater Rockmaster (Diphlebia lestoides)

The Chalky Patroller

This species is named for its habitat—it loves the “whitewater” riffles and rapids.

- Where to find them: Widespread across Queensland, New South Wales, and Victoria.

- Identification (Male):

- Colour: Instead of the “electric” blue of the Sapphire, the Whitewater male is often a softer, chalky blue or grey-blue.

- Wings: The absolute giveaway is a milky-white bar or streak across the wings (pterostigma area). This flashes visibly when they fly against dark water.

- Tail: The tip of the tail often looks like it has been dipped in solid, matte blue paint.

- The Female: A subtle mix of brown and buff colours.

Quick ID Tip: Look for the white bar on the wings. No other Rockmaster has this feature so clearly.

4. The Giant Rockmaster (Diphlebia hybridoides)

The Rainforest Relic

As the name suggests, this is a massive, robust insect. It is an icon of the deep rainforest.

- Where to find them: Restricted to the Wet Tropics of North Queensland (e.g., Daintree, Mossman Gorge).

- Identification (Male):

- Body: Very thick and robust. The pattern is a mix of blue-grey and black.

- Wings: The most defining feature is the bold dark bands or panels across the wings.

- Behaviour: They are often less flighty than other species, relying on their camouflage in the dappled rainforest light.

Quick ID Tip: If it’s huge, in the rainforest, and has banded wings, it’s the Giant.

5. The Arrowhead Rockmaster (Diphlebia nymphoides)

The Inland Explorer

While the others hug the coast, the Arrowhead loves the rocky gorges of the interior.

- Where to find them: Inland streams and rivers of Queensland and New South Wales (e.g., Carnarvon Gorge).

- Identification (Male):

- Abdomen: Distinctly striped! Unlike the solid black/blue tails of the others, this one has clear blue rings down the length of the abdomen.

- Markings: Named for the arrowhead-shaped black mark on the top of the blue abdominal segments.

- The Female: Shows the arrowhead markings clearly in shades of brown.

Quick ID Tip: Look for the striped tail (rings of blue and black) rather than a solid colour.

Why Rockmasters Matter

Finding any species of Rockmaster is a good sign. Their young (nymphs) live underwater beneath stones and require clean, highly oxygenated water to survive. They are sensitive to pollution and sedimentation.

If you see these brilliant blue flashes in your local creek, it means the ecosystem is functioning well!

A Note on Scientific Accuracy

The classification of Australian damselflies is a specialized field. We align our naming conventions with the Atlas of Living Australia and the CSIRO. Distribution maps and specific taxonomic details are sourced from the work of dedicated Australian odonatologists.